Press

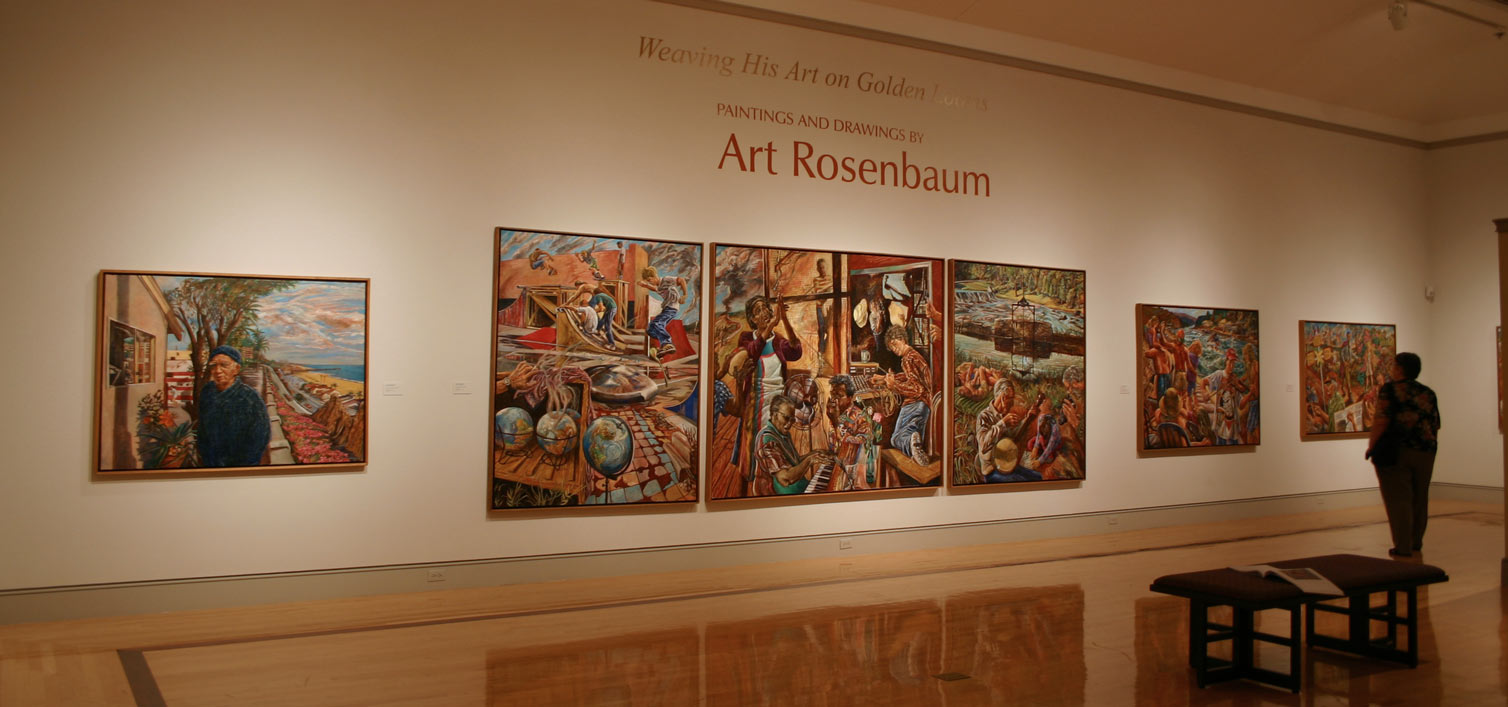

Telling Tales: A Portrait of Art Rosenbaum

by Dennis Harper

“Art Rosenbaum has a lot of fun

Playing his banjow [sic] in many tunes

Weaving his art on golden looms.”

(The Reverend Howard Finster)

In 1981, Art Rosenbaum asked Howard Finster to suggest a title for an exhibition in which they were both included, a survey of contemporary artists working in Appalachia. Finster promised over the telephone, “I’ll cut off all my brain cells but one” to get it done, and a scant week later Rosenbaum had an illustrated list in hand containing ninety suggestions. The exhibition’s curators at the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, passed over many fine, unmistakably Finsterian title prospects — Art of the Hidden Seens; Tail [sic] of the Artist to [sic] Long to Tell; Artist of All Kinds Stair [sic] up Many Minds — and chose instead a line from one of his songs. But the document held several jewels, including the reference to Rosenbaum’s musicianship and artistry that provides the fitting title of the present exhibition.

Rosenbaum quotes Howard Finster occasionally: in the classroom, on stage, over a drink. He can also pull out a bon mot appropriate to almost any situation, recalled from Paul Cézanne, John Singer Sargent, or Titian. Although one of Rosenbaum’s academic colleagues has accused him of composing the “quotes” himself on the spot, he swears they are authentic. He has seen them before, somewhere. The lines stuck in his mind and now provide ready material for his erudite yarns. In much the same way, Rosenbaum’s paintings deliver a profusion of visual quotes and cultural references woven into their tales, encounters that have been subsumed into the artist’s instrument to emerge in complex and richly-layered canvases. His stories, both in word and paint, evince an untiring, inquisitive mind.

Finster’s brief but poetic titular verbal image aptly evokes a rich fabric and a precious implement. The Georgia Museum of Art’s retrospective examination of Rosenbaum’s paintings is an attempt to enhance Finster’s picture and heighten awareness of an artist who eloquently celebrates a vibrant, creative world. Transcribing that world onto canvas, Rosenbaum populates his elaborate tableaux with vernacular artists of all stripes, public and private musicians, storytellers, visionaries, lovers, and — significantly — observers. His paintings go beyond a simple notion of narrative art, spinning tales and interlacing imagery in surprising ways that frequently confound easy interpretation and yet coalesce in ineffable, lyrical rightness and clarity. Rosenbaum synthesizes diverse elements as a part of his process, making connections that add up to more than the sum of their parts. “[Vasily] Kandinsky said [that] a creative mind can use anything, even a spent match stick,” Rosenbaum explains. “You can take something from the everyday and start with that.”

Rosenbaum’s version of “everyday” is, without doubt, remarkable. In his paintings, one is proffered entry to a kaleidoscopic view of not-so-ordinary people, doing the things they are moved to do by their muses, through the Holy Spirit, or simply for the sheer fun of it. Rosenbaum has likened himself to the archetype of the Wandering Jew, whom he inserted prominently in Old Cornelia Highway, 1999 (cat. no. 42). His itinerant observer, though, is not a cursed figure, but one who roams the world collecting experiences. We are pulled along as fellow travelers. Sometimes Rosenbaum’s paintings seem to draw the spectator into the composition as if he or she were a participant in their goings-on, while with other paintings the viewer remains a voyeur, even observing the observer within a scene. Rosenbaum craftily depicts himself as a doppelgänger within many compositions, recording his subject on film, tape, or canvas.

Rosenbaum acknowledges the unsung by documenting artists and traditions outside the mainstream. For instance, Rosenbaum’s visual portrayals of African American ring shout participants on the Georgia Coast, who welcome the New Year in a ritual of song and gesture, or his treatments of North Georgia fiddlers and folk artists, together with his audio recordings of and writings on the same subjects, have given those individuals deserved attention, often bringing them to the larger public’s eyes and ears for the first time. In the process, he has frequently elevated his subjects to near-mythic stature through grand pictures of history-painting proportions such as Wind and Water, 1988 (cat. no. 27) and Rakestraw’s Dream, 1990 (cat. no. 28). Encompassing more than fifty years, Rosenbaum’s art is now due its own focused scrutiny and greater recognition. Finster’s use of language was never naive and always required a closer look. Perhaps he thought of Rosenbaum when he penned his “Tail of the Artist to Long to Tell.” Rosenbaum’s “loom” has been quite busy and its production far from ordinary; indeed, it is a story one longs to tell.