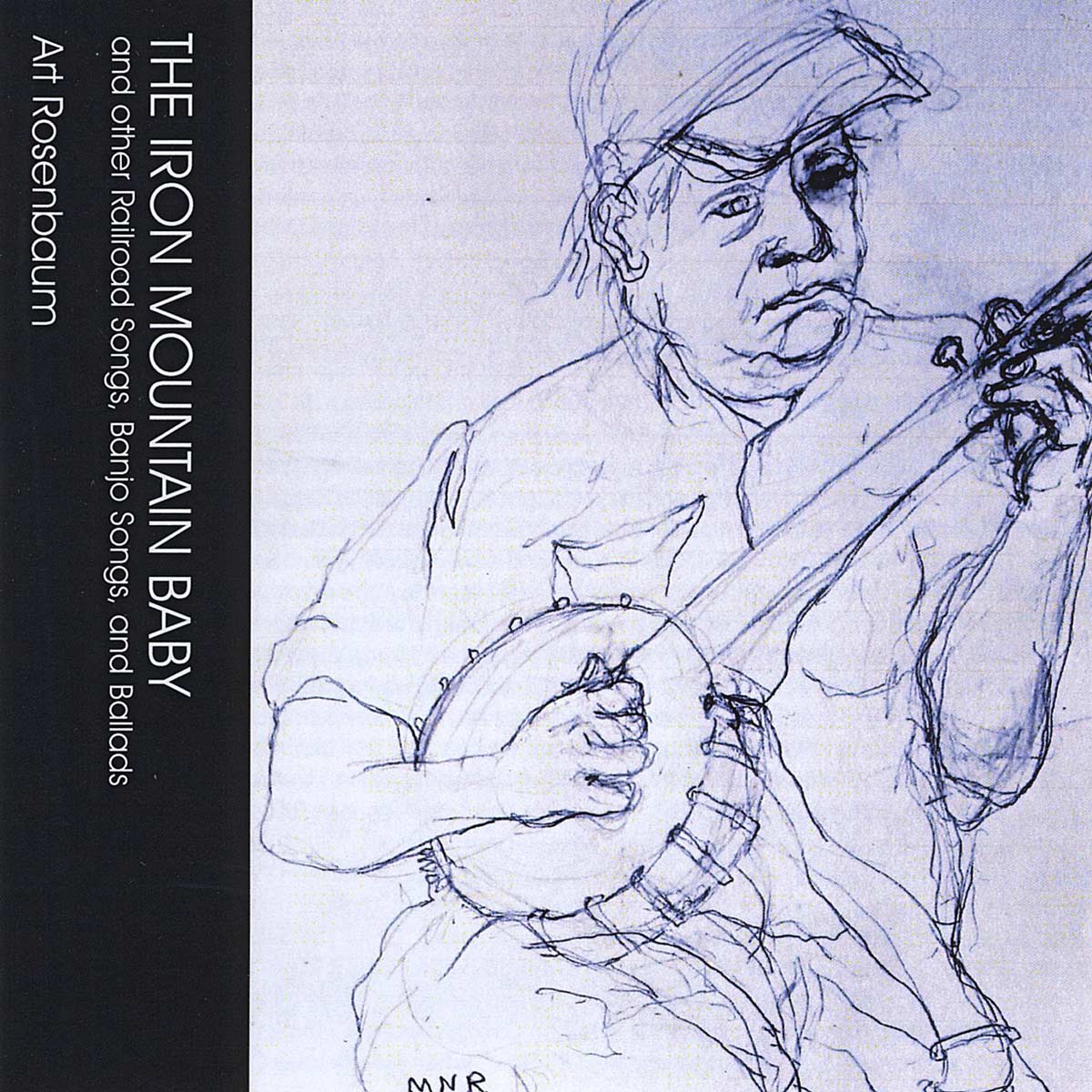

Iron Mountain Baby and other Railroad Songs, Banjo Songs, and Ballads

American folk songs and tunes sung and played with banjo, guitar, fiddle, harmonica, by veteran performer solo and with friends; traditional, and performed in traditional style, many were learned first-hand during the artist's field collecting.

Genre: Folk: Traditional Folk

Release Date: 2015

Description

“I have a song I would like to sing, it’s awful but it’s true,”

So begins the title song of this collection of songs and ballads–and two banjo solos. Most of the old story songs were based on actual events, as was THE IRON MOUNTAIN BABY; and the non-narrative blues and lyric songs were and remain true as well, in a human and poetic sense, often deep and even “awful”, though occasionally ironic or humorous.

On August 14, 1902 a satchel containing an infant was thrown from the northbound Number 4 of the Iron Mountain & Southern Railway in Washington County, Missouri; it was found by elderly Civil War Veteran William Helms, who with his wife cared for the injured baby. They raised the child who, happily, went on to live a long life. The ballad was composed by one William T. Barton. I picked up most of it from traditional singer Rev. Jim Holley of Illinois.

Through no special plan, the railroad crops up in several songs that I have been singing and playing recently; certainly America’s railroads, evoking wandering, disaster, dislocation, longing, lost love, and “journey-proud” adventure, figured mightily in so many of the songs and ballads of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that especially appeal to me.

NINE HUNDRED MILES FROM MY HOME is certainly of African American origin, part of the vast “Ruben”, “Train 45” family widespread among black and white folk singers and musicians in the South; my version leans to Georgia, with verses from Fiddlin John Carson and Riley Puckett.

ROLL ON, BABE comes from another song cluster, black railroad and mining work songs, adapted by white mountain banjo pickers,“Roll on John”, “Nine Pound Hammer”, and more.

CANNONBALL BLUES was adapted by A. P. Carter of the original Carter Family from a song sung and played by his black friend, Leslie Riddle, and this is my reworking.

THE WORRIED BLUES is obliquely a railroad or hobo song, adapted from North Carolina banjo picker Samatha Bumgarner’s song, recorded in the early 1920s, with a related song,“Georgia Blues” on the flip side of the 78; both are part of another large song family played and sung by blacks and whites: “Goin’ Down This Road Feelin’ Bad”, “Lonesome Road Blues,” and Darby and Tarlton’s “Down in Florida on a Hog.”

The oldest song here is GEORGIE, a British ballad (Child 209). There is disagreement over the historical basis of this story of a maiden trying to save her well-born but miscreant lover, but most likely there is one. My rendition is from the Arthur Kyle Davis collection of Virginia ballads, transcribed from the singing of S. F. Russell.

I learned another song with roots in Britain, a lovely lyric song, HUSH MY LOVE AND DON’T YOU CRY, from ballad singer sisters Mary Lomax and Bonnie Loggins who live in north Georgia; they got it from their father, Lemuel Payne, who was born in 1884.

ADAMHAM TOWN, replete with surrealistic images of impossible quests and “a world turned upside down” originated in England as “Nottingham Town”, moved to Kentucky as Jean Ritchie’s “Nottamun Town”, and strangely became “Adamham Town” in the huge repertoire of Arkansas ballad singer Ollie Gilbert. (I spent a wonderful afternoon with her years ago recording her ballads, but didn’t hear this piece; it comes from a recording by folklorist Max Hunter.)

One more almost “crazy” song from the British Isles, in this case, Ireland, is THE GREAT HIGH WIND THAT BLEW THE LOW POST DOWN. I first heard Bob “Fiddler” Beers (who had it from his Irish grandfather in Minnesota) sing it at Gerdes Folk City in New York, and was recently reminded of the verses by Pat Shields. I recorded the fiddle variant, that Beverly Smith joins in on, from Indiana fiddler John W.“Dick” Summers; he learned it from his friend Matt Simond, who had no name for it.

If “Georgie” is the oldest song on the collection, then BOOGIE-WOOGIE BOOGER is the newest. It was composed by The Myers Sisters, Helen Myers McDuffie, Molly Myers Moody, Margie Myers Roberts, and Leasie Whitmire, Helen’s daughter, of Apple Pie Ridge near Baldwin, GA.

The sisters learned many traditional songs from their father in the North Georgia Mountains, and were gifted in making their own songs in older and newer country modes. Here old dances like the double shuffle and dances of the sisters’ younger years like the rhumba and the boogie-woogie mingle, and are performed by a wacky menagerie of animals at a moonshine still, while their old hound dog gets drunk (they swore this happened.)

A rougher song of drinking is the banjo “rounder” song PASS AROUND THE BOTTLE, the lament of a young man who ruins his life by hard drinking and fighting; it was recorded by Alan Lomax from the singing and banjo picking of Kentuckian Walter Williams.

In a lighter vein is RIPPYTOE RAY; I found it in Ira Ford’s “Traditional Music in America”, and it is probably from the Ozarks. It’s a short ditty, as are the songs in the medley of SHORT SONGS. Some of my favorite American folk songs have but one or two verses, but these can be funny, wry, wise, evocative, poetic.

“Sing, Sing” is sung by Bonnie Loggins, who learned it from her banjo-picking brother, Charles Harmon Payne; I picked up “Who’s Been Gettin‘ There?” in Iowa from Harry “Pappy” Wells, a fiddler from the Missouri Ozarks (the tune is “Shortnin‘ Bread’); Ruth Crawford Seeger found “Of All The Beast-es in the World” in the Library of Congress collection of field recordings and included it in her book “Animal Folk Songs for Children”; “Greenville Street” was sung and picked on banjo by my friend Ed Teague, whose grandparents had sung played it in Rabun County, Georgia.

I think the oddest way I ever “caught” a song was “My Old Fiddle and My Old Bow”, when elderly Iowa City fiddler Charlie Drollinger passed out from heat exhaustion at a house party. Revived as paramedics were carrying him away to be checked out, he cheerily sang “My old fiddle and my old bow/The best old fiddle in the county-o” to assure his worried friends that he was ok; I learned “Mammy Black Cat” from Dr. Ben Barrow of Athens, Georgia, who sang it with his daughters Nancy and Betty; “My Little John Henry” was recorded by John and Alan Lomax from the singing of James “Iron Head” Baker in the Sugarland Prison in Texas in 1933; I found “Roll Them Simmons” in a Depression-era Federal Writers‘ Project collection of Mississippi folk songs.

I guess I place myself in a small way in the “banjo-songster” continuum, a solo voice with banjo, which flows from West Africa and the American banjo’s cousins and ancestors through the ante-bellum South into the Southern mountains and beyond. Kentuckian George Gibson grew up knowing a player who said “if you can’t sing it, don’t pick it”, and yet another great Kentucky singer and banjo-picker Roscoe Holcomb was proud that he once could sing verses to every one of the over two hundred banjo pieces he knew.

There are however banjo solos in the older repertoires, and I do like to pick straight banjo pieces, here SALLY JOHNSON, which I learned from Chesley Chancey of Gilmer County, Georgia; and SNOWBIRD, which I learned playing along with left-handed Georgia mountains fiddler Ross Brown (he learned it as a boy from a blind fiddler, Joe Swanson), along with THE BIG SCIOTA a West Virginia fiddle tune I worked out for banjo.

Still, good verses go with good banjo tunes, and SHOUT LULU, probably of African American origin, is the archetype, and it— or its cousin, “Hook and Line”—was most often the first piece Southern banjo pickers learned. I got the version here from W. Guy Bruce from a place that used to be called Screamersvillle in Chattooga County, Georgia; and I try to bring to it some of his verve. His set of verses is the best I’ve heard.

Banjo songster or no, I do like playing with other musicians and am grateful that friends Beverly Smith, with fiddle and mandolin and harmony vocals, John Grimm on guitar, and Paul Lombard on slide guitar, joined me on some tracks here.

POOR HOWARD was a signature piece of Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter, one of the first he learned as a teen-ager playing at sukey-jump country frolics in Louisiana. Of course he played it on 12-string guitar (his first instrument was the squeeze-box), but I try it on seven-string banjo.

This instrument, set up like a five-string banjo, has a short drone or “thumb string” but six rather than four longer melody strings. It enjoyed some popularity in the late 19th century but was usually a stage or parlor instrument, and the only evidence I have found of it in folk tradition is a verse in an Afro-Caribbean sea chantey, “Oh, the banjo, the seben-string banjo, dance girl, gimme the banjo!”