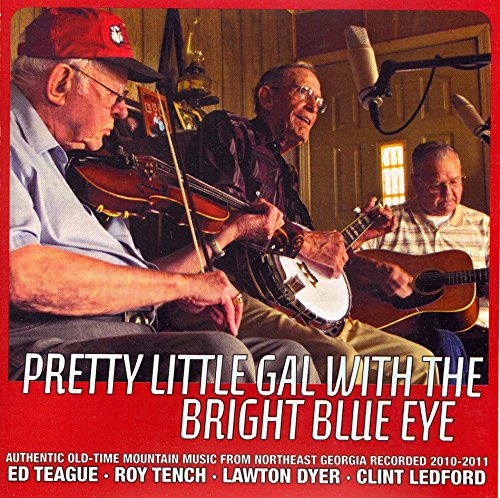

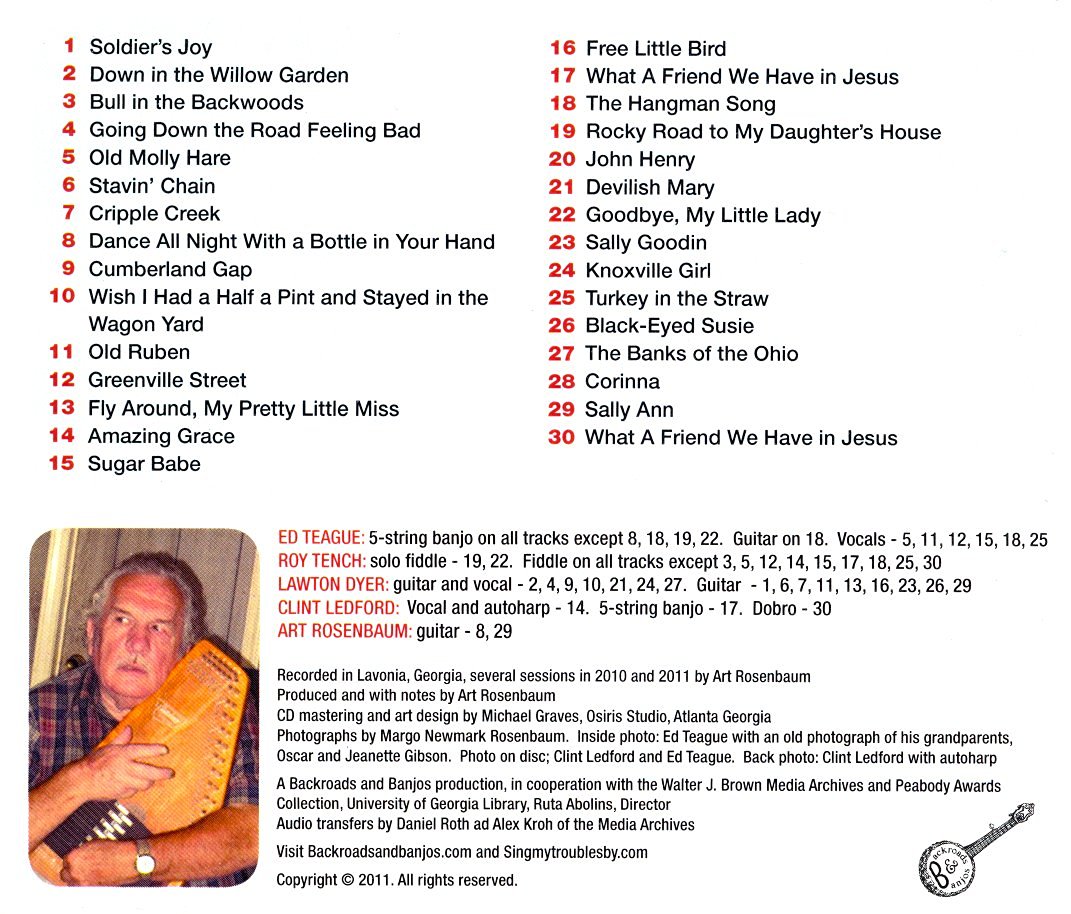

Pretty Little Gal With the Bright Blue Eye: Authentic Old-Time Mountain Music from Northeast Georgia

Here is a collection of mountain music, performed by four fine older gentlemen from the north Georgia mountains who treasure the styles of music they grew up with.

Description

As I went down to Greenville Street, pretty little gal I chance did meet.

“Oh my lover, are you travelin’?” “No, by guineas, I’m a-goober-grabblin’!”

Bye and by, I’m gonna marry ‘fore I die, pretty little gal with the bright blue eye

I had known Ed Teague, a fine old-time two-finger banjo picker from Rabun County, Georgia, for over 30 years before I heard him pick his banjo and sing “Greenville Street,” a little gem of a song he had learned as a boy up in the mountains of Rabun County from his grandfather, Oscar Gibson. It was from Gibson also that Ed got his wryly hilarious set of verses to “Old Molly Hare,” some verses to “Turkey in the Straw” and “Sugar Babe,” as well as the banjo tune “Bull in the Backwoods” (sometimes called “Too Young to Marry,” “Buffalo Nickel,” among scores of other names.)

Ed’s grandfather, who played banjo, fiddle, and organ, and had a fine voice and a great store of old songs, also sang in harmony with his wife, Jeanette: one, that Ed sings here with guitar, was a poignant song that “made the hair stand up on the back of your neck”, according to Ed—despite its happy ending– the old ballad of British origin, “The Hangman Song” (“The Maid Freed From the Gallows”, Child #95).

He did remember one verse of “Greenville Street,” and in case you are wondering, “goober-grabblin’” means picking peanuts.Ed considers himself to be mostly an old-time string band banjo picker, but consented to have some of his songs as well as banjo tunes included on this CD so they would not be forgotten—he observed that “a tremendous amount” of the old music has been lost, including many songs, and verses of songs, his grandparents sang, which he cannot bring back to his memory. He did remember one verse of “Greenville Street,” and in case you are wondering, “goober-grabblin’” means picking peanuts.

Early field collectors of Appalachian music did not work in North Georgia as much as in mountains of neighboring Tennessee and North Carolina; and commercial recording companies in the 20s and 30s who were very active in Georgia did not, for the most part, seek musicians in the northeastern part of the state: there were plenty of fine old-time fiddlers and musicians closer to Atlanta, such as the Skillet Lickers, Earl Johnson, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Ahaz Gray.

Surely some fine music would have been recorded from Oscar Gibson and his musical friend, Bert Myers. Ed heard his grandfather and Myers play together often, and just a few years ago ran into three older ladies who played old-time music at Hamby Mountain Music Park, asked them if they weren’t “Bert Myers’ girls” and resumed a musical friendship with the family. After Margie Roberts and Molly Moody died in a car accident in 2003, surviving sister Helen McDuffie reorganized the group as “The Myers Family and Friends,” with Ed playing banjo. Sadly, Helen passed away in October, 2011.

Another musical connection of interest: Ed’s wife, Hazel’s, great aunt was Eva Davis of North Carolina, who with her friend Samantha Bumgarner (both women played fiddle and banjo), made some of the first commercial old-time country recordings in 1924; Ed and Hazel remember her as a colorful lady who could “cuss like a man.”

Although his family had a big apple orchard, times were hard, work was grueling, and home-made music, on the back porch or at neighborhood square dances, provided the main entertainment for family and community.Ed was born on May 28, 1927, on a farm on Black’s Creek in Rabun County, near Rabun Gap, in the northeast corner of Georgia; his parents were Louie Teague and Lula Gibson Teague. Although his family had a big apple orchard, times were hard, work was grueling, and home-made music, on the back porch or at neighborhood square dances, provided the main entertainment for family and community. They did own a battery-powered radio, and Ed remembers his grandfather listening to The Grand Old Opry when it featured old-timers like Uncle Dave Macon and Sam and Kirk McGee, supplementing his traditional repertoire with their music.

Ed learned guitar and banjo at a young age, and played with his brothers at square dances and neighborhood gatherings. During his working years he was a truck driver, but he always treasured his music, and in retirement has taken every opportunity to jam or play at local events and festivals with other mountain-style musicians.

When I first met him he was playing in a duo with guitarist, singer, and entertainer Ray Knight. In the ensuing years he was a member of The Crazy Mountain Boys, The Georgia Mountain Boys which included Lawton Dyer, finally a band appropriately called Ed Teague and Friends. They have issued several self-produced cassettes and CDs over the years.

Ed’s musical roots and associations were mainly local, and although he played music from the age of 5, he never aspired to be a full-time professional; he notes that many who did this felt compelled to modernize their

music, something he refuses to do. However, Ed is an outgoing man and he has gotten around in country music circles, having met well-known musicians like Bill Monroe, Ralph Stanley, The Lewis Family, Snuffy Jenkins, Wade Mainer, and Snuffy Jenkins. Has played a set with the Dry Branch Fire Squad, and with Red Rector. He has performed at the Knoxville World’s Fair in 1982, the Georgia Grassroots Festival, and the North Georgia Folk Festival.

Lawton Dyer knew Ed as fellow truck driver for many years before discovering that they shared an interest in old-time music, and they have played together since about 1980. Lawton was born in Banks County, Georgia, on August 14, 1933. His father played fiddle and pump organ, and Lawton, who tried to play “Black Smoke A-Rising” on the guitar at the age of 4, says he got “pretty good” by about 13 or 14.

Lawton’s singing has an ease and warmth reminiscent of Wade Mainer’sHe loved the recordings of the original Carter Family, Mainers’ Mountaineers, the Louvin Brothers, as well as the Gid Tanner’s Skillet Lickers. He credits Ed with encouraging him to get over bashfulness in singing, to add vocals to their music. To my ear, Lawton’s singing has an ease and warmth reminiscent of Wade Mainer’s.

When I recorded fiddler Gordon Tanner, guitarist Smokey Joe Miller, and banjo picker Uncle John Patterson in 1982, John proudly announced that we had assembled the prototypical old-time string band, with “one on fiddle, one on guitar, one on fiddle.” For this recording I got fiddler Roy Tench fill out a trio. He has known Ed for a few years but had not played with him until recently.

Besides having grown up with traditional music, Ed and Roy have other things in common: both are World War II U.S. Army veterans, Ed having guarded German prisoners at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and Roy having been an anti-aircraft gunner serving in Normandy (he landed 9 days after the invasion), in the Battle of the Bulge, and in Germany; they also have the same birthday, May 28, although Roy is five years older, born in 1922 (they had a joint birthday party in 2011 attended by 15 or more musicians.)

Roy grew up in the Mud Creek section of Habersham County (just down the road from Lem Payne, an old-time ballad singer who taught his still-living daughters Mary Lomax and Bonnie Loggins many fine old songs), and worked the family farm until he quit farming a few years ago. Both his parents played fiddle, and he started playing at the age of six. He credits his mother, Mary Jane Teach, with having been his main mentor, although he learned the two unusual tunes he plays here, the breakdown “Rocky Road to My Daughter’s House” and the waltz “Goodbye, My Little Lady,” from his father, John Henry Tench.

Like Ed, he played for Saturday night square dances. Although he has listened to a considerable amount of recorded fiddle music, his playing is still the bluesy, syncopated and swinging old-time Georgia style, and he can play in old-fashioned “cross-tuned” tunings. He enjoys playing out in public, and not long ago played at a local winery and at the lookout point at Tallulah Gorge for over three hours each, hardly stopping and not repeating a tune.

Roy and Lawton take it more or less in stride that their style of music has garnered more interest of late: Roy says, “it’s something different” for the young people, and Lawton says the same, while pointing out that people of his age group have “known it all along.” Ed basically agrees, but will go further in articulating why he plays the style of music he does. He does not like Bluegrass musicians who seem to be competing with others when they play; you have to be “your plain old self and let it go at that.”

His banjo style is a simple up-picking, where the index finger plays a lead melody note, followed by the same finger brushing down and the thumb hitting the 5th string on the off-beat, with hammered and pulled notes adding to but not over embellishing his clear and sensitive choice of notes. Unlike his grandfather and other Georgia and North Carolina two-finger pickers, he does not bring the thumb to the inside strings, “double-thumbing.” He considers himself a “noting” rather than a “chording” player, seldom fretting more than one string at a time.

When playing with others he listens to them closely to make his playing complement theirs.All in all, his style and tone are clear; when playing with others he listens to them closely to make his playing complement theirs. He and Hazel have warmly welcomed people from near and far, including England and France, to their home outside of Lavonia. Some of these visitors are interested in learning his style: recently a lady brought her 17 year-old grandson to visit–he wanted to learn to play like Ed–and Ed told me, “the little booger can do it pretty good!” He recently heard from a girl in Tennessee who has not come to see him yet, but told him he was “all over the internet” (this was probably a clip from my son Neil Rosenbaum’s documentary video “Sing My Troubles By”).

Joining Ed on some tracks is another musical friend, Clint Ledford, of Clarkesville, Ga. Born in Shooting Creek, North Carolina in 1942, Clint is a nephew of Kentucky banjoist and singer of the Coon Creek Girls, Lily Mae Ledford. A retired law enforcement officer, Clint has taught himself to play numerous instruments over the years, including piano, dobro, autoharp, and recently, banjo, but not the guitar—“everybody plays guitar.”

His features clearly show his American Indian ancestry—his grandmother, Rachel Garrett, of Caney Fork, North Carolina, was a full-blooded Cherokee and taught him the verses of “Amazing Grace” in the Cherokee language, which he here accompanies on autoharp.

Ed was his mentor on banjo, but despite his efforts to emulate Ed’s style, he worked out a 3-finger lick which he uses in an unusual banjo duet with Ed, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus”—after all, “everyone’s got their own style.”

Here is a collection of mountain music, performed by four fine older gentlemen from the north Georgia mountains who treasure the styles of music they grew up with. Besides tracks mentioned above, there are well-known square dance tunes like “Black Eyed Susie”, “Soldier’s Joy”, “Sally Ann,” “Cripple Creek,” and “Dance All Night With a Bottle in Your Hand”; an Americanized murder ballad of British origin, “Knoxville Girl” and two American murder ballads, “Banks of the Ohio” and “Down in the Willow Garden.”

The famous ballad about the steel-driving man, “John Henry” is played as a fiddle-banjo duet, as is the bluesy “Corrina.” “Stavin Chain” is a song of African American origin, learned from Burk Carver, who lived on neighboring Kelly’s Creek (Ed says the title is a corruption of “slaves in chains”); as is “Old Ruben.” “I Wish I Had a Half a Pint and Stayed in the Wagon Yard” is a song that Gordon Tanner claimed was composed by his uncle, Arthur Hugh Tanner, and was recorded by other Georgia musicians, notably Earl Johnson.

“Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad” is ubiquitous in one version or another in the repertoires of black and white Southern folk musicians, and became the anthem of the migrants of the Dust Bowl years. “Devilish Mary” was recorded by the Skillet Lickers and also Roba Stanley of Dacula, Georgia, the first woman to record a solo vocal with guitar.

Old-time mountain music lives on in the hands and voices of talented singers and musicians in Appalachians and beyond; but in the second decade of the 21st century there remain few who, like Ed, Roy, Lawton, and Clint, grew up when traditional picking and singing was a mainstay of family and community life. We thank them for “hanging in,” as Ed puts it, with their treasured music. Ed says simply, he is “proud to keep the old-time music alive.”

– Art Rosenbaum, 2011